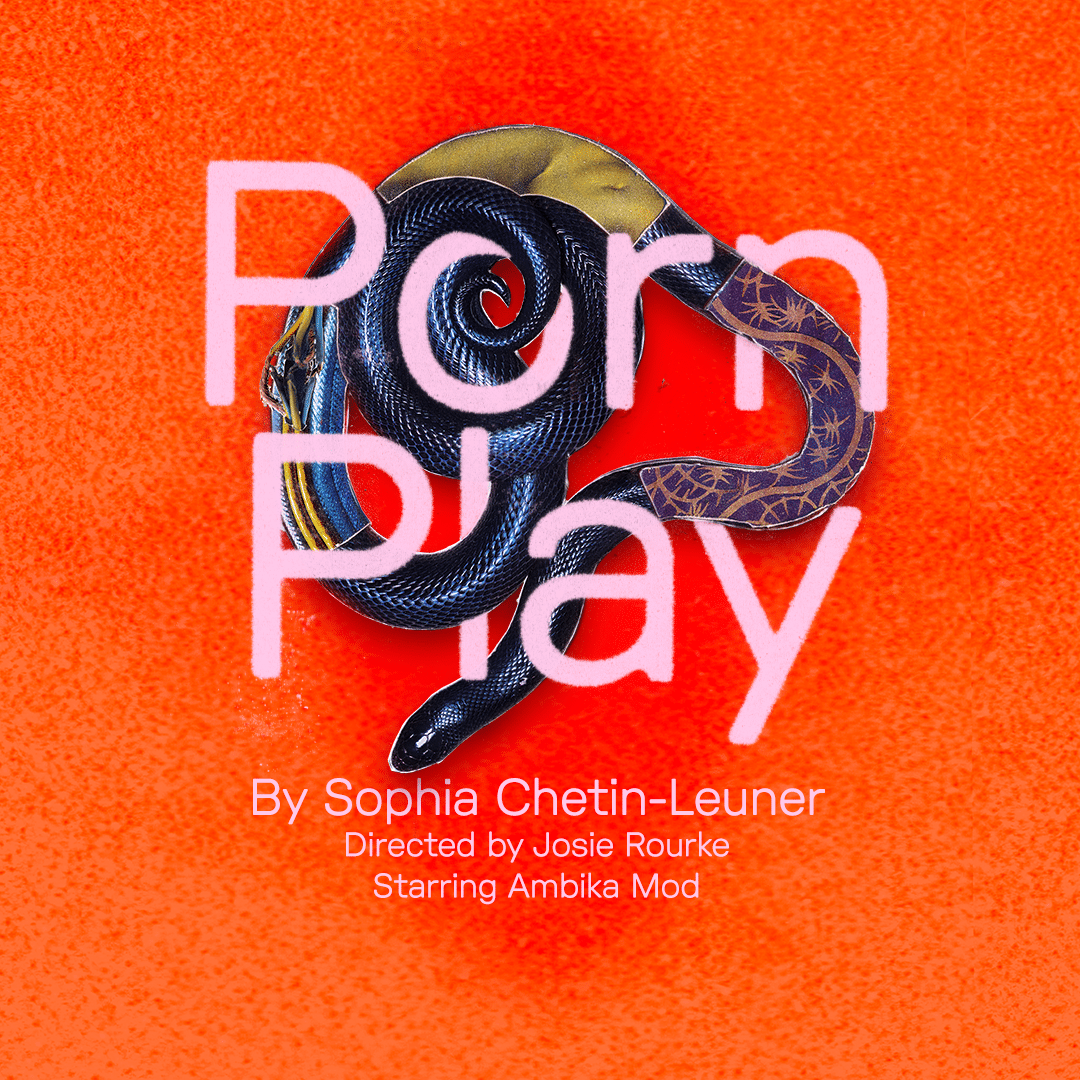

Porn Play Isn’t Really About Porn: A Review

In this guest blog, Harriet Jackson, our Communications Manager, dives into Porn Play, a bold, darkly funny exploration of porn addiction, grief, and fractured relationships.

Guest blog by Harriet Jackson, Communications Manager (and theatre lover)

Walking into the Royal Court Theatre with Paula to watch Porn Play, I expected a provocative and possibly uncomfortable afternoon. I was cautiously optimistic that the overall message would be compassionate, though I wondered if we might end up in a quagmire of moralising about pornography. What I didn’t expect was a production that would deftly sidestep the trappings of “a play about porn” and instead offer a stark, tender, and at times very funny exploration of pain, relationships, and the ways we cope with life’s wounds. Sophia Chetin-Leuner’s script is bold in its subject matter but surprisingly delicate in its emotional intelligence. The result is a play that doesn’t wag a moralising finger at its audience, nor does it glamorise the darker edges of porn consumption. Instead, it sits in the mess of it – sometimes gently, sometimes with brutal honesty.

At its centre is Ani (played flawlessly by Ambika Mod), a rising academic star who is articulate, witty, and put together, but carrying a secret addiction to violent pornography that is slowly unravelling her life. On paper, it sounds sensationalist, but on stage it is anything but. By the time we reach the more extreme moments (masturbating beside a sleeping friend, slipping away from her awards ceremony to be alone with her phone) it feels less like watching something “outrageous” and more like witnessing someone drowning in plain sight.

The play paints a world around Ani that is recognisably human. Her partner (played with wounded sincerity by Will Close), gives voice to a struggle we see often with couples facing porn addiction: what do you do when your partner’s sexual interests feel confronting, even frightening, yet you don’t want to shame them? Close portrays the discomfort, attempts at open-mindedness, confusion, and heartbreak of living with someone whose compulsive behaviour erodes intimacy.

Meanwhile, Ani’s friendship with her best friend (a warm and frequently hilarious Lizzy Connolly) brings moments of buoyancy to the story. Their scenes provide some lovely humour: affectionate, quick-fire, and full of the mundane truths of friendship. This makes Ani’s violation of that friendship (masturbating in bed beside her) feel all the more like a betrayal.

Her father is portrayed by Asif Khan with an almost devastating quietness. Through glances, pauses, and fragmented conversations, we begin to understand the crater in Ani’s life left by her mother’s death. The grief is palpable but mostly unspoken, lodged in the kind of generational silence that leaves young people alone with their pain. Khan’s restrained performance captures a father who loves his daughter but doesn’t know how to help her – perhaps the most heartbreaking relationship in the play.

One of the play’s unexpected triumphs is its refusal to offer easy answers. Ani’s one attempt to seek help leads her to a 12-step-style meeting that derails into a kind of mansplained motivational seminar. The attendee we meet is a parody of internet masculinity (also played by Close) – spouting jargon and veering wildly between support (“Do you want help?”) and exclusion (“You’re too triggering for the guys”). He’s absurd but, regrettably, not entirely unrealistic. Many people seeking help for porn problems encounter groups or mentors who conflate abstinence and moral purity with sexual wellness.

The GP scene takes aim at the awkwardness of sexual health care: scratchy blue paper, the attentive-yet-false tone of doctors, and a bureaucratic approach to intimate pain. Yet beneath the humour lies a genuinely harrowing revelation – Ani’s compulsive masturbation is causing recurring vaginal infections, and she must abstain entirely to heal. Mod’s expression – a mix of horror and grief – silences the room of any laughter from the moments before.

What becomes clear over the course of Porn Play is that porn is just a supporting character here, not the lead and certainly not the whole story. Like compulsive porn use in real life, it functions as both escape and sedative – a behaviour that promises relief from emotional overwhelm and instead compounds it. The play hints at classic hallmarks: loss of control, escalation, impaired sexual intimacy, shame, withdrawal from relationships, work consequences, even physical harm. But it never collapses Ani into a case study. She remains a full, complicated human being whose addiction is not an identity but a coping mechanism.

And this complexity matters. Public discourse around porn addiction often swings between outright dismissal (“porn addiction isn’t real”) and puritanical alarmism (“porn is evil and should be banned”). What’s missing is nuance, and Porn Play offers nuance in abundance. It acknowledges the very real suffering caused by compulsive use without slipping into moral panic. It reminds us that shame is not evidence of wrongdoing; shame is often evidence of pain. And it challenges the assumption that porn-related struggles are exclusively a male issue.

It comes at a timely moment as public figures like Ore Oduba have recently spoken about their own struggles with porn addiction, helping broaden the conversation and reduce stigma. This play pushes that door open further and insists that we look beyond the behaviour and ask what’s going on underneath.

If all this makes Porn Play sound heavy, it is – but it is also warm, disarmingly funny, and full of compassion for its characters. The humour is never cynical as it lifts the heaviness without trivialising it. The performances are excellent, and Chetin-Leuner’s script is full of raw and relatable life – the ugly and the beautiful.

By the end, I wasn’t left thinking primarily about porn addiction. I was thinking about grief and loneliness. About the slipperiness of coping mechanisms that we tell ourselves are harmless and how easy it is for intimate pain to go unspoken until it erupts into self-destruction. And about how many people, like Ani, are navigating these struggles in silence.

Porn Play is not a play about porn so much as a play about the stories we tell ourselves to cope, and what happens when those stories stop working. It is brave, necessary, and surprisingly tender. And, perhaps most importantly, it brings the conversation about compulsive porn use further out of the shadows. Honest, compassionate, and unafraid to look directly at the pain beneath the behaviour, it is exactly the kind of work we need.

Need support?

If you’re starting to question your porn-use and feel like you might be struggling with compulsive behaviours, why not take our “Am I an Addict” questionnaire.

For those that know they need support now, take a look at our suite of online support programmes.